The flag of Kent was included on the registry from its inception. The design of a white horse rearing on its hind legs has been associated with the county for at least four centuries, whilst the common origin story pushes it back over a thousand years.

One school of thought postulates that the white horse of Kent derives from the ancient white horses cut into chalk downs and stamped on the coins of more than one pre-Roman British king; these

are from the reign of Dubnovellaunus of the Cantii or Cantiacci tribe, from whom the name of Kent derives, from c. 30 to 10 BC

are from the reign of Dubnovellaunus of the Cantii or Cantiacci tribe, from whom the name of Kent derives, from c. 30 to 10 BC

A more common tradition links the emblem with the first Germanic invaders in Britain, Jutish mercenaries from the Danish peninsula, led by brothers Hengist and Horsa: the pair appear in the 9th century work on the history of the English people, “Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum” by the Venerable Bede; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; the 9th century work attributed to the Welsh Monk Nennius, “Historia Brittonum” and Geoffrey of Monmouth ‘s 12th century “Historia Regum Brittaniae”. All these works of course were completed centuries after the events they describe and the two brothers may well have been legendary, the theme of twin brothers appears frequently in Germanic stories as recorded by classical writers and additionally the horse was an important element in the rituals of many ancient peoples, with names derived from the words for horse appearing frequently – the Old English words “Hengest”and “Horsa” meant respectively, “stallion” and “horse”. Conceivably, these founding fathers may in fact have been just the one individual, which is suggested by the similarity of these two names with equine associations. Reflecting all these characteristics, these Jutish invaders were said to have borne a banner bearing a white horse and it is further speculated that the symbol may have referred to the mythical horse Sleipner, which belonged to the god Odin, venerated by these Germanic warriors. The story of Hengist and Horsa further relates that the latter was killed in battle with the Celtic leader Vortigern at Aylesford, where a monument was raised in his honour, the White Horse Stone

near Maidstone. This standing stone is considered by some visitors to resemble a horse’s head. Apparently the site has also been known locally as “The Ingá stone”, which presumably could be a corruption of the name “Hengist”?

As with Essex, the emblem of this early English kingdom was first recorded in print in the 1605 work “A Restitution Of Decayed Intelligence”

by Richard Verstegan, which included an engraving of Hengist and Horsa landing in Kent in 449 under the banner of a rampant white horse.

It is worth noting that the illustration specifically shows a flag bearing a horse rather than a shield, a clear assertion that the invading force specifically used a flag with the horse emblem. The same theme appeared in the 1890 work “A Popular History Of Germany.’ by William Zimmermann,

where the rampant steed is seen adorning the sail of the vessel bringing the invaders to the island.

Whilst it is an appealing notion that Jutes arrived on the shore of Kent brandishing a white stallion over their heads, as romantically depicted by Richard Verstegan, the truth is that there are no grounds to support it and the idea is firmly put to bed by James Lloyd in his 2017 work “The Saxon Steed And The White Horse Of Kent”, volume 138 of “Archaeologia Cantiana” the journal of the Kent Archaeological Society. In the modern era a white horse is found on the insignia of several continental territories which are broadly whence the Jutes sprang, these include;

Lower Saxony, Germany

North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Twente, Netherlands

Twente, Netherlands

and in fact the heraldic motif of the “Saxon Steed” is a recognised trait in German civic heraldry, originating in the continental “Duchy of Saxony”. One theory holds that the Saxon Steed originates either from the white horse reputedly ridden by the Saxon leader Widukind after his baptism – formerly he had ridden a black one – or again, as a representation of Odin’s horse Sleipnir. But as Lloyd reveals, the Saxon Steed motif was an anachronistic promotion of the fourteenth century, later associated with the Germanic peoples of the fifth. A running or “courant” horse, was present on the seal

of Duke Albrecht I of Brunswick and Lüneburg, of the House of Welf/Guelph, upon his accession in 1361 he made armorial use of this device, that is, deployed it on a shield, as a coat of arms. The horse theme was subsequently embraced by all branches of the family, with that used by Duke Magnus from 1369, depicted rearing on its hind legs

although with two back feet planted on the ground, in a more natural realisation termed heraldically, “forcené”. This compares with a rampant stance

where the horse is shown rearing with only one foot touching the ground, rarely seen in nature

and usually occasioned by fright or combat, and salient,

where both the back feet are resting on the ground but both front legs are illustrated as if level with each other.

The horse was inherited by succeeding individuals and administrations, leading to its modern civic usage. It is James Lloyd’s contention that the Duke purposefully promoted the equine symbol to lend substance and venerability to the claim of the dukes of Saxe-Wittenberg in the electoral procedure of the Holy Roman Emperor. He relates how Bede’s description of Hengist and Horsa was elaborated upon by a fifteenth century German writer named Gobelinus Person who asserted that they were sons of the Duke of Enger, in Saxony and that they bore the insignia of a horse as canting arms, i.e. visual references to their equine names, depicted on their arms. Person writes of how existing nobility in the locality perhaps “received such arms from their progenitors from ancient times.”. Historical references to early Germanic personages with equine names, were thus used to fashion similarly equine insignia, for political gain and empowerment. James Lloyd writes “… the founders of the kingdom of Kent who had given the dukes of Brunswick the idea for the Saxon Steed.”: it is intriguing that figures who had departed German shores were used for this purpose but their status as the source of the Saxon Steed theme seems further evidenced by an apparent local house building tradition. A common decorative feature on the roofs of farmhouses in the states of Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein are gables shaped as horse heads

which, it is reported, as late as 1875 were apparently referred to as “Hengist and Hors” Although notwithstanding the names, the tradition may conceivably reflect a more ancient Germanic rite, associated with horse shaped or horse associated figures.

By this analysis it appears that Verstegan, who had moved to the continent, became acquainted with the myth that leaders in Saxony used equine arms inherited from their forbears and that the same set of emblems had been taken by their kinsmen on their migration to Kent. Before his account no such association is apparent but following Verstegan, John Speed included the white horse

on the title page of his 1611 “Atlas of Great Britaine”. It further appears several times on a map of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy

It is shown twice at left, as part of a decorative column flanking the map, which depicts the “founders” of the kingdoms,

and once on a right facing red shield held by “Hengist”

The white horse of Kent is also shown twice on this page on a blue shield, once on the opposite column beneath a scene depicting the conversion of King Ethelberht

and again over the kingdom of Kent on the actual map part of the page

Speed features Kent’s horse,

again in his “History Of Great Britaine” (also from 1611, reprinted in 1623) and it further appears there in quasi flag or banner form

The stallion appeared in print again the following year, on the frontispiece of “Poly-olbion”, presented as a topographical poem describing England and Wales, by poet Michael Drayton. The cover shows Britannia, clothed in a robe, amidst “historical” figures from the nation’s past; Brutus, Caesar, William of Normandy and Hengest,

depicted alongside a red shield, bearing the white horse of the kingdom of Kent, which he was held to have founded

Whether in Kent or on the continent, the rearing stallion is predominantly shown against a red background but such variations as Speed’s are not uncommon. Another example of the horse with a blue background can be found at Ightham Mote, country house, shown below and interestingly this arrangement is repeated in the badges of several of the county’s modern sporting associations, also below. James Lloyd alludes to the possibility that Speed’s variation may have followed German practice where the steed is sometimes seen on a blue shield. He further writes “It is unclear if this distinction in background was intended to represent the conversion to Christianity or was an irrelevant fancy.” Another intriguing suggestion for the varying red and blue depictions of the shield’s colour is the discrepancy of hatching marks, used to indicate colours in printed works where colour was unavailable. The system of marks was almost universal save for amongst Dutch printers, prolific in producing maps and charts, who often transposed the marks for red and blue. It has also been reported that some 19th century versions of the Kent arms even occasionally included a green strip of turf below.

Whether in Kent or on the continent, the rearing stallion is predominantly shown against a red background but such variations as Speed’s are not uncommon. Another example of the horse with a blue background can be found at Ightham Mote, country house, shown below and interestingly this arrangement is repeated in the badges of several of the county’s modern sporting associations, also below. James Lloyd alludes to the possibility that Speed’s variation may have followed German practice where the steed is sometimes seen on a blue shield. He further writes “It is unclear if this distinction in background was intended to represent the conversion to Christianity or was an irrelevant fancy.” Another intriguing suggestion for the varying red and blue depictions of the shield’s colour is the discrepancy of hatching marks, used to indicate colours in printed works where colour was unavailable. The system of marks was almost universal save for amongst Dutch printers, prolific in producing maps and charts, who often transposed the marks for red and blue. It has also been reported that some 19th century versions of the Kent arms even occasionally included a green strip of turf below.

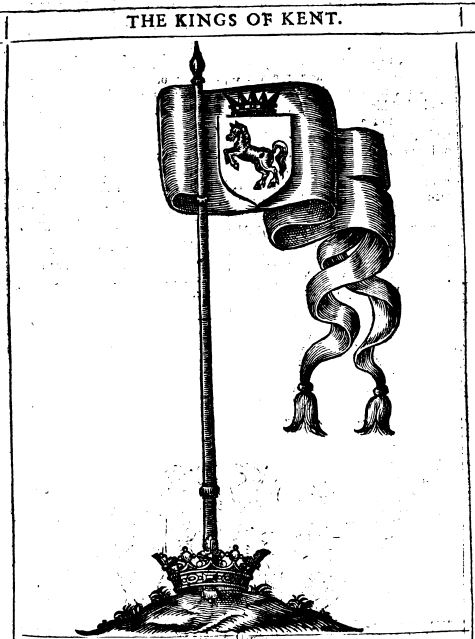

The horse then featured as the emblem of the Kingdom of Kent in “Divi Britannici”

by Sir Winston Churchill (direct ancestor of the famous twentieth century one), published in 1675.

By the eighteenth century, the Saxon Steed which had been adopted by the House of Welf in the fourteenth was included, in a running or “courant” depiction

in the arms of the Elector of Hanover, who was of this dynasty. A red flag bearing a running white horse

was used as an unofficial civil flag in Hanover until 1837 and the recognition of the symbol is demonstrated today by a bronze statue in Hanover city

A modern version of the Hanoverian horse.

In 1714 the elector Georg Ludwig acceded to the British throne as George I and upon his enthronement the Royal British coat of arms was altered to accommodate his Hanoverian arms

including the “Saxon Steed”. The reported ancient Jutish symbol, had thus “reappeared” in Britain as the symbol of a national leader!

It then appeared on the masthead of the county newspaper, the Kentish Post, which first featured it in 1722

, eight years after the German monarch’s accession, definitively marking the rampant white stallion as a symbol of the county of Kent. Another example of such usage, from 1726, is seen below

A practice maintained by subsequent local publications through the centuries

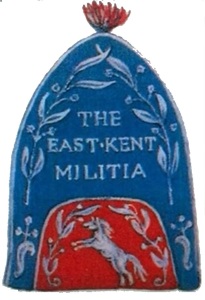

A Royal Warrant issued by George I’s successor, George II, in 1751, ordered the display of the Hanoverian white horse on military caps and equipment. Lloyd points out that the order applied to the military as a whole but that pointedly the version used by East Kent Militia showed a rearing horse, presumably, in reference to the arms of Hengest which had appeared in the works of Verstegan and Speed. A forcene style horse is present on this regimental mitre cap

A Royal Warrant issued by George I’s successor, George II, in 1751, ordered the display of the Hanoverian white horse on military caps and equipment. Lloyd points out that the order applied to the military as a whole but that pointedly the version used by East Kent Militia showed a rearing horse, presumably, in reference to the arms of Hengest which had appeared in the works of Verstegan and Speed. A forcene style horse is present on this regimental mitre cap

while a salient horse is seen on this image of an East Kent regimental badge

while a salient horse is seen on this image of an East Kent regimental badge

from circa 1830. Similarly, officers of the West Kent Militia wore sash buckles with a salient white horse – thus the tradition of displaying the white horse on Kentish military uniforms was established. George I’s accession to the British monarchy was not universally popular but this protestant monarch was welcomed in Kent, which had a strong Protestant tradition. There was also an obvious similarity between the attributed arms of Hengest, founder of Kent and those of the House of Hanover. In the words of James Lloyd “By purportedly reviving a symbol so clearly related to George I’s ancestral arms, the Men of Kent advertised the ancient links between their county and his homeland and, more importantly, flaunted their Protestant credentials and their support for the Protestant king.”

Thus, following the examples of the county newspaper and local military, the ensuing. century saw the white horse emblem popularly taken up by a wide variety of county based organisations and companies. Tradesmen issued tokens bearing the white horse

and it was adopted by the Kent Insurance Company in 1802, for its fire plate

and it was adopted by the Kent Insurance Company in 1802, for its fire plate

, used to mark properties subscribing to the company’s fire fighting service, also appearing at its Canterbury headquarters;

interestingly the former in a forcené stance, the latter, rampant.

William Berry’, who had determined the blazon of the arms of Kent as “gules, a horse salient, argent,” that is, red with a white rearing horse, in his 1828 “Encyclopaedia Heraldica”, featured the rearing stallion on the cover of his 1830 “Pedigrees Of The Families of The County Of Kent”

and it made a resplendent appearance on Thomas Moule’s 1836 map of the county

and it made a resplendent appearance on Thomas Moule’s 1836 map of the county

as well as appearing on the masthead of another publication, in 1852, which covered several counties, “The Sussex Advertiser”

It is also of note that a rearing steed is present in the artwork “Vortigern and Rowena”

by William Harvey, dating from around 1848, depicted on a banner at the top right of the scene and based on a tale which describes Rowena as a daughter of Hengist!

Further 19th century examples of the emblem’s association with the county are found on the sacks, “pockets”, used by Kentish hop pickers

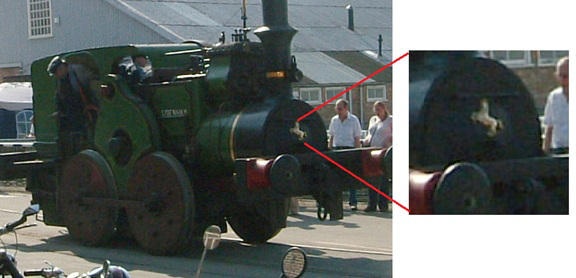

and its usage by the Rochester based firm Aveling and Porter, producer of agricultural engines and steam rollers, which bore the white horse of Kent at the front of its vehicles

A further example

is found amongst the collection of the Cobb family, a prominent local family of the era, while another is present on this panel

from a county brewery and the white horse is present in this array

located at the Crossness Pumping Station, in Bexley in the county, completed in 1865. The emblem of the Metropolitan Board of Works which built the station, it incorporates various arms and emblems including the three seaxes of Middlesex, indicating the board’s territorial remit encompassing areas from these counties.

Another example of the white horse is found at the Chapel Corridor of Ightham Mote in the county, amongst some stained glass panels depicting coats of arms

including one attributed to the kingdom of Kent’s celebrated king, Ethelbert

where the background colour is distinctly blue, which may have been directly influenced by the Speed depiction under Ethelbert’s conversion, as described above.

The white horse is also present on the insignia

of the company operating rail services in the county.

And the popularly acknowledged county device continued to be used by county based military units

including, as seen above, on a blue coloured pennant device, by the West Kent militia. However it was forged, the link between the emblem of a white horse and the county of Kent was demonstrably established by the nineteenth century.

Another county based body to make use of the white horse was the Kent Archaeological Society

founded in 1857. Kent County Council, although also established in the nineteenth century, in 1889, surprisingly, did not receive a formal grant of arms depicting the acknowledged county emblem

until 1933, on the 17th of October. The blazon of the shield, “gules, a horse rampant argent” i.e. red with a white rearing horse, is one of the simpler heraldic descriptions. The same design of a rampant stallion over the motto “Invicta” had, however, been used as a seal

by the body, since its inception in 1889, under the legend “Kent County Council” with the date “1889” in base. This pattern was both applied to wax,

in the ancient, traditional method, to seal documents and also used as a stamp

as on this 1916 licence,

where it also appears at the top of this official council document, effectively as a quasi coat of arms or early form of logo. The combination of white horse and “Invicta” motto also decorated the 1901 publication “Picturesque Kent” by Duncan Moul and Gibson Thompson

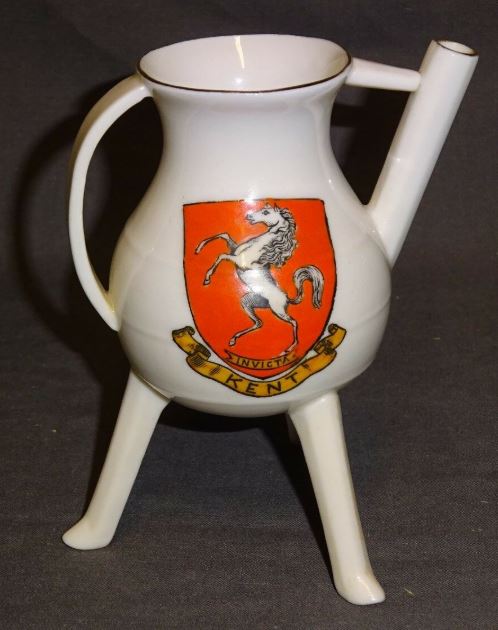

and is present on this example of Goss ware china

from the early twentieth century.

The motto “Invicta”, seen on these examples and the council arms and also included in the emblems of the railway and insurance companies shown above, means ‘unconquered’, in Latin and refers to a local legend which holds that in 1067, shortly after the Norman Conquest, a detachment of Kentishmen ambushed the newly crowned King William; in return for his life, he promised that the county would be able to keep its ancient privileges, the “Treaty of Swanscombe”, thus Kent was the only part of England deemed “unconquered” by the Normans. This motto is thus also a popular theme in the county and the county flag is accordingly sometimes referred to as the Invicta Flag or Invicta Flag of Kent. The defiant rearing stance of the horse lends itself naturally to the description, invicta!

Having been in the public domain long before the creation of the council and generally acknowledged as representing the whole county as an entity in itself, as demonstrated for example, by its appearance on the Moule map, such long recognised arms and an armorial banner formed from them, could not be restricted to the council’s use but represented the whole county as an entity in itself. In the twenty-first century therefore, the Flag Institute accepted that an armorial banner was the county flag, on the basis of this traditional association and use.

The display of the white stallion as a flag appears to have begun with Kent Cricket Club founded in 1870. It has been speculated that the red flags seen in the background of the famous cricket painting ‘Kent v Lancashire’, painted by Albert Chevallier Tayler in 1906

may be flags of Kent but this has not been confirmed. The club was certainly using the device for its own badge at this time

However, the flag is unequivocally present over the ground, seven years later,

at a Kent v Sussex match, captured in film coverage of the event. The design appears to match the club badge seen on the above programme, with the rearing stallion depicted over the INVICTA motto.

A reference to the flag of Kent, unearthed by James Lloyd, was made by German author Richard Andree, in his ‘Braunschweiger Volkskunde, 2nd ed. (Brunswick, 1901), pp. 173–4, ‘ a work first published in 1896. Lloyd’s translation, following, relates that while writing about the ‘national’ symbol (as used in Hanover) the author cites its usage overseas in the English county of Kent, although he again cites the fallacious ‘legend’ of the Kent flag’s origin,

‘The flag of Kent in England, the white horse on the red field, completely agreeing with our arms, shows how widespread the national symbol is and can be proven. It is Hengest himself, who founded the kingdom of Kent in 455, who by the conquest of England must have brought over this flag with the steed.’

As further revealed by James Lloyd, Lord Harris, the second captain of the club in 1870, was, in 1931 (61 years later!) chairman of the council body tasked with securing it formal arms. From his experience with the flag at the cricket club, Harris prevailed on the choice of red for the council’s arms, which he asserted was more visible when the weather was inclement, suggesting, given the Speed and other variations with a blue field colour, that a flag with a blue background might also have been tried and that a version with a blue background for the council arms may also have been under consideration.

James Lloyd also relates that in 1936, the cricket club’s flag was used to represent Kent at an inter-county chess competition; county identities are often most egregious in the form of cricket clubs (!), a notion somewhat borne out by further records cited by James Lloyd, held in the Kent History And Library Centre, suggesting that even in 1952, the red flag bearing a white stallion was regarded as the cricket club’s flag, i.e. not the general flag of the county of Kent. However, whoever entertained this misapprehension was clearly not aware of the flag’s wartime deployment.

Kent’s trenchant association with the white horse was further solidified with its usage during World War II by the RAF’s “County of Kent” Squadron, No. 131. Kent was the only county to have had a squadron of its own as a result of large donations made by the people of Kent. The full story of the squadron can be found here. Inspired by the Maidstone based Lord Cornwallis, large funds were amassed to purchase a number of Spitfires. Acknowledging the donations Lord Cornwallis spoke of “…blessing and protection for these glorious men who are riding on the wings of the White Horse of Kent”

Lord Cornwallis presented two flags to the squadron, one bearing the motto “Invicta” and the other, the white horse of Kent.

Another example of a Kent flag,

believed to have been flown by a Medway vessel. And a further marked instance of the flag’s usage was its appearance in a procession through Rye, just over the county boundary in Sussex,

during a Bonfire celebration, in November 1973.

during a Bonfire celebration, in November 1973.

Further evidence unearthed by James Lloyd, somewhat shockingly indicates that the county of Kent might have paraded quite a different emblem altogether. A mediaeval manuscript (Harley 2169) whose origins date to the reign of Henry VI (1421-1471), includes a set of arms ascribed to the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, the seven kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon era from approximately the late fifth century to the ninth. Remarkably, the arms featured in this work for the Kingdom of Kent depict three seaxes! White on a red background.

Lloyd submits two theories regarding this pattern. Conceivably, the mediaeval herald who completed this work, following the contemporary practice of referring to Hengest and Horsa as generic “Saxons”, may have invented the seaxes as “canting arms“, a common heraldic practice. The herald assigned these to Kent on the grounds that that was the first “Saxon” kingdom to be established. Alternatively, the design may commemorate a gruesome but significant chapter in the annals of the founding of the kingdom, the so-called “Treachery of the Long Knives“, recorded by Nennius and made famous by Geoffrey of Monmouth, when Hengest’s forces, gathered to negotiate with the Brittonic (British or ancient Welsh) ruler Vortigern, concealed their seaxes under their cloaks. Hengest is reported to have cried out “Nimat eowre seaxes”, (Take out your seaxes.) as the signal for his men to kill the Britons. The herald who devised the arms bearing these three seaxes may have had this infamous incident in mind. James Lloyd’s conclusion regarding Richard Verstegan’s assignment of the white horse to Kent, suggests that having done so, Verstegan then re-assigned the above three seaxes emblem to Essex based on the etymological link between the name of that kingdom and the seaxes depicted!

Lloyd submits two theories regarding this pattern. Conceivably, the mediaeval herald who completed this work, following the contemporary practice of referring to Hengest and Horsa as generic “Saxons”, may have invented the seaxes as “canting arms“, a common heraldic practice. The herald assigned these to Kent on the grounds that that was the first “Saxon” kingdom to be established. Alternatively, the design may commemorate a gruesome but significant chapter in the annals of the founding of the kingdom, the so-called “Treachery of the Long Knives“, recorded by Nennius and made famous by Geoffrey of Monmouth, when Hengest’s forces, gathered to negotiate with the Brittonic (British or ancient Welsh) ruler Vortigern, concealed their seaxes under their cloaks. Hengest is reported to have cried out “Nimat eowre seaxes”, (Take out your seaxes.) as the signal for his men to kill the Britons. The herald who devised the arms bearing these three seaxes may have had this infamous incident in mind. James Lloyd’s conclusion regarding Richard Verstegan’s assignment of the white horse to Kent, suggests that having done so, Verstegan then re-assigned the above three seaxes emblem to Essex based on the etymological link between the name of that kingdom and the seaxes depicted!

The arms awarded to Kent county council in 1933 were reconfirmed for the successor administration, whose remit does not cover the full extent of the county. In addition to its official arms, the modern council uses a simplified logo derived from them

The white horse also appears on the civic coats of arms of many of the county’s towns and cities, either as a charge on the main shield, as part of the crest over the shield or as a supporter, including;

Ashford, Beckenham, Bexley

Bromley, Dartford, Deptford

Dover, Gravesham, Lewisham

Maidstone, Medway, Sevenoaks

Swale, Tonbridge, Tunbridge-Wells

A white horse is the main charge on the coat of arms of the University of Kent

and a similar set of arms is used by Kent Collge,

and taking the lead from the county council, it appears on the badge of Kent Fire and Rescue Service.

and Kent Police

as well as on the official arms of the High Sheriff of Kent

Unsurprisingly the white horse is also found on the arms of the Kent County Society

A magnificent depiction of the Kent emblem in stained glass

is found at Canterbury cathedral and another

can be seen at Saint Mary’s church, Reculver.

And a notable appearance of the Kent emblem is found on a plaque alongside one bearing the Sussex martlets

which are today on the wall of a school in Tunbridge Wells on the Kent/Sussex border,

but were formerly to be found on the Kent and Sussex Hospital

which occupied the site previously and served both counties. Both county emblems also appeared on a badge worn by staff working there.

Kent’s rearing stallion also appeared on another badge worn by nurses at a county hospital

And in the late twentieth century, coach firm “Invictaway”, which ran London bound commuter coaches from the county, cleverly combined the popular Kentish Invicta motto in its name with the white horse emblem in its logo

Several Kentish sporting bodies also include the white horse on their badges. Kent Cricket Club’s former badge, seen here

Several Kentish sporting bodies also include the white horse on their badges. Kent Cricket Club’s former badge, seen here

as a wall plaque, was a conventional depiction. This was replaced in 2010 with

a modern logo with a graded colour scheme of red to blue. Whilst the club stated that the new arrangement reflects its “traditional colours of maroon and blue”, the pattern recalls the aforementioned advice to Kent council of Lord Harris in 1931, to opt for a red background, with the implication that blue may have also featured in the club’s history. And certainly blue is the colour of choice for several of the county’s other sporting bodies, including Kent Football Association, Kent County Football League and Kent Rugby Football Union.

Perhaps the blue preference reflects the nineteenth century origin of these bodies when this variant was more common, such as seen amongst military units. Kent football club Gillingham, previously displayed the white horse alone, also against a blue background but now includes it as one element in its badge.

The county symbol also appears on the badges of many other Kent clubs, examples of these can be seen on this page. In 2020 Kent Cricket Club adopted a new badge, with an entirely red background

The county’s famed white stallion, against a more common red background, is also the insignia

of Sittingbourne based Kent Kings speedway team and is suitably amended with a hail of arrows

on the emblem of the county’s archery association. Although the emblem of the West Kent Archery league again places the county’s rearing stallion against a blue background!

Interestingly, Kent’s white horse has been adapted as a “house flag” by the vessel Medway Queen, famed for its exploits at Dunkirk during World War Two and now sited at Gillingham pier. The design places the rearing steed against a background divided red and blue!

Whilst ‘White Horse’ is not an uncommon name amongst British pubs, in Kent, where it carries a greater significance, it is particularly popular! Some examples are in

Cranbrook, Bridge and, Dover;

Bearstead, Borstal and Boughton;

Chilham, Edenbridge and Faversham,

Headcorn and Rainham;

Sundridge and Otham

and Hawkinge;

with another in Bilsington which makes a particular highlight of the county emblem

Kent’s treasured emblem is also frequently found atop village signs in the county, over simple, white, name signs

and more elaborate pictorial devices

with a particularly elaborate version at Langton Green

and occasionally where the horse is present without the red background

The county emblem is present on the War Memorial in Tenterden

and is commonly found, as a decorative feature on its typical Oast Houses, although, seemingly for ease of visibility, these are black in colour!

The continuing recognition and popularity of the white horse as the symbol of Kent is demonstrated by the presence of a large white horse design cut into the hillside overlooking the town of Folkestone and the English terminal of the Channel Tunnel

, which was completed in June 2003. The horse was planned as a Millennium landmark and designed by a local artist, Charlie Newington. Similarly, but on a much grander scale, was a proposed project to erect a 50 metre/160 feet high sculpture of a white horse

in Ebbsfleet Valley in the county. Designed by Mark Wallinger to faithfully resemble a thoroughbred horse, the structure would be visible from both the A2 road and High Speed 1 railway line, which cross each other nearby.

Kent’s flag being a simple white horse against a red background, the realisation of the design is open to wide interpretation. The horse depicted on the Flag Institute registry is a rather flamboyant illustration

but in practice the majority of commercially available Kent flags

appear to be based on the logo used by Kent County Council and are much simpler in stylisation as the following examples of the flag flying around the county demonstrate

This version of the flag has also been used in a sporting context and to identify locally made products

and can often be seen aloft in the county

and further afield; below, in Yorkshire, Sussex and Lincolnshire

Further examples of the flag of Kent in use include; its appearance over Lords cricket ground during a match against Middlesex

; another during the Last Night Of The Proms celebrations!

; its proud hoisting at the Glastonbury music festival

its enthusiastic take up by the county airsoft team

and its deployment on the kit of the East Kent Morris Men

A humorous version of the flag

created by cartoonist Dave Chisholm, including the county’s “INVICTA” motto and referred to as “Hengist” (!) flew over Whitstable Castle and it is seen here

alongside the flag of its neighbour, Surrey.

As well as the stylisation of the horse, both the shade of red of the background and placement of the horse emblem, also vary to some degree. On the design of the Kent flag found on the registry, the horse is placed off centre, closer to the hoist, this is to allow the figure to appear at the centre when the flag is in a full gust of wind. Again, in practice most available flags do not observe this precise positioning and simply place the horse at the centre of the flag, as can be seen in these various examples  Such varying stylisations, including one at left with the horse offset, are occasionally seen in flight

Such varying stylisations, including one at left with the horse offset, are occasionally seen in flight

In 2011 it was the logo style version of the flag that flew outside the Eland House Headquarters of the Department For Communities and Local government in London,

Whilst the registry version of the horse is highly detailed, the logo style version is too simplistic and insubstantial; a happy medium is the version favoured on these pages ( available here )

which is taken from issue 92 of Flagmaster, the journal of the Flag Institute

and is likely to have been based on the depiction located in the 1933 work “Civic Heraldry” by C.W.Scott-Giles

itself reflecting the various depictions of the horse found around the county on plaques and signs and the county arms that adorn the Kent County Council building in Maidstone.

This Kent stallion is is also present on the ensign

and burgee

of the Medway Yacht Club.

This page has undergone extensive revision following the 2017 publication of “The Saxon Steed And The White Horse Of Kent”, volume 138 of “Archaeologia Cantiana” (the journal of the Kent Archaeological Society) by James Lloyd, from which a deal of evidence and several conclusions have been taken. Acknowledgement of and thanks for, this scholarly investigation are duly given.

Thanks are also due to Brady Ells for additional images and information.

Useful Links